Head First: Concussion concerns and safety protocols in school rugby

Piers Francis of the Blues gets medical treatment after a concussion during the 2017 Super Rugby match.

Image: Gavin Barker, BackpagePix

As the school rugby season kicks into gear across South Africa – with the prestigious Wildeklawer Schools Tournament around the corner – players, parents, coaches, and referees are bracing for high-intensity clashes. But behind the thrill of every try and tackle lies a growing concern: head injuries.

Rugby, a physically demanding contact sport, carries a real risk of brain trauma – from mild concussions to more serious traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). While the game fuels school pride and sporting excellence, experts are urging schools to prioritise player safety, especially when it comes to concussion management.

Understanding the Risks

Dr. Hofmeyr Viljoen, a radiologist at SCP Radiology, says the most common head injury in rugby is concussion. “It occurs when the brain is jolted inside the skull due to an impact or violent movement. Some cases may seem mild but can lead to significant short- and long-term effects,” he explains.

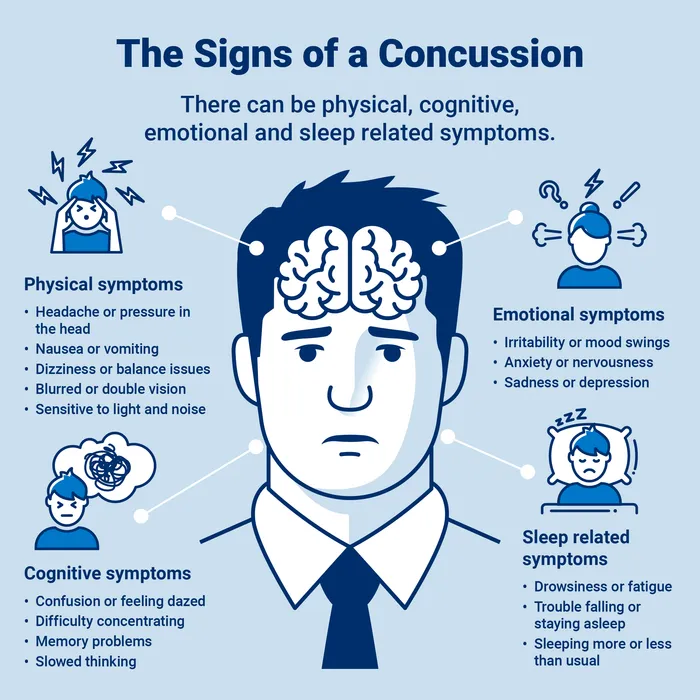

Warning signs such as dizziness, confusion, headaches, nausea, and memory lapses should never be ignored. “Players showing any of these symptoms must be removed from play immediately to prevent further harm,” Viljoen says.

In emergency settings, CT scans are the go-to method to rule out skull fractures, brain swelling, or internal bleeding. However, for persistent or subtle symptoms, advanced MRI techniques – such as Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) – can detect injuries not visible on a CT scan.

Symptoms to be aware of when a head injury is expected

Image: Supplied

Local Insight: How Diamantveld High School Tackles Concussions

In Kimberley, Diamantveld High School has taken a proactive approach. Head of Rugby Oloff Bergh says the school officially implemented World Rugby’s Head Injury Assessment (HIA) protocols at the start of 2025.

“In the event of a suspected head injury, we immediately perform an on-field assessment using the Maddock's questions. If the player fails to respond appropriately, they are removed for a more detailed off-field evaluation,” he explains.

The school then applies the HIA1 assessment. If the player passes and there’s no clinical suspicion of concussion, they may return to play after 12 minutes – except in Blue Card cases, which mandate removal. Any abnormal findings result in a referral for medical evaluation, often including a CT scan.

If cleared of concussion, players can return with a doctor’s note. If a concussion is confirmed, the Gradual Return to Play (GRTP) process kicks in: 14 days of rest followed by a structured five-day progression of light training. If symptom-free through all six stages, the player may return to the field on day 19 post-injury.

The process is overseen by Bergh and team members Wilmi and Sven, who manage assessments and recovery records. Junior and senior players are monitored throughout each recovery phase, with clearance only granted when all benchmarks are met.

Fitness expert Rian Willers, responsible for emergency medical response, has completed World Rugby courses in concussion awareness, spinal injury management, and first aid.

Bergh stresses the importance of education: “We recently held a session with all our coaches to walk through the concussion protocols and clarify each person’s role. It’s vital that everyone involved understands how to protect our players.”

The Bigger Picture: Serious Complications and Long-Term Risks

Dr. Viljoen warns that ignoring concussion protocols can lead to devastating consequences. One such risk is Second Impact Syndrome (SIS) – a rare but often fatal condition where a second concussion, sustained before recovery from the first, causes rapid brain swelling and respiratory failure.

“Young athletes are particularly vulnerable,” he says. “That’s why strict return-to-play procedures are non-negotiable.”

There’s also the long-term threat of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain condition linked to repeated head injuries. Although CTE is currently only diagnosable after death, ongoing research is exploring how imaging techniques like Positron Emission Tomography (PET) may help identify markers in living patients.

Prevention Starts on the Field

The most common causes of head injuries in school rugby include dangerous tackling, awkward falls, and accidental collisions. According to Dr. Viljoen, early education in proper technique is key: “Teaching safe tackling from a young age is one of the most effective forms of prevention.”

Bergh agrees: “Education, early diagnosis, and consistent enforcement of protocols can prevent many of these injuries. While protective headgear can reduce superficial wounds, it does not prevent concussions – which is why awareness and medical vigilance are so important.”

Ultimately, both experts agree: rugby continues to be a powerful platform for teaching teamwork, discipline, and resilience. But the health and safety of young players must always come first.

Related Topics: