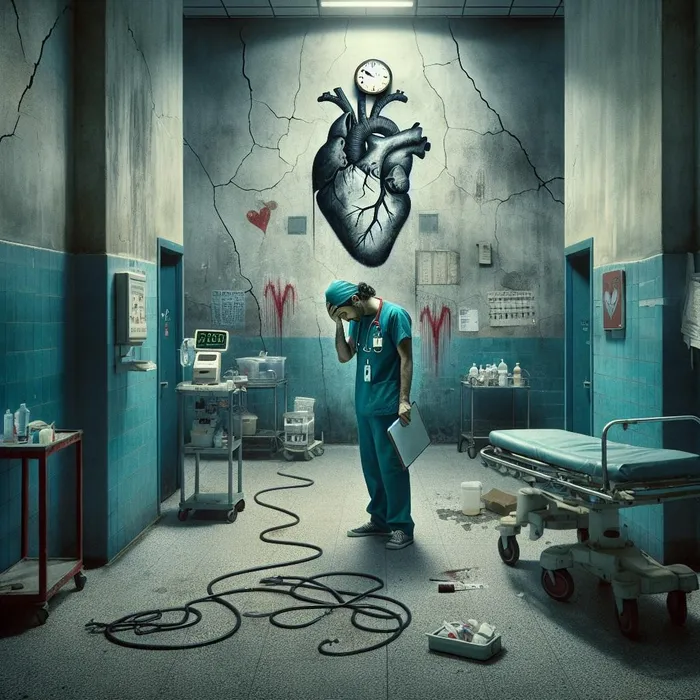

Corruption and Chaos: The year South Africa's health system crumbled

Healthcare Reform

In 2025, South Africa's public healthcare system faced an unprecedented crisis, grappling with severe staff shortages, rampant corruption, and alarming surgical delays, putting countless lives at risk and igniting nationwide protests for change.

Image: IOL / Ron AI

In 2025, South Africa's public healthcare system faced profound strain as chronic issues of staff shortages, critical infrastructure failure, crippling surgical backlogs, and pervasive corruption reached breaking point.

While the government announced limited recruitment and budget boosts, these efforts were widely regarded as insufficient to stem a tide of deterioration that placed patient lives at risk daily.

At the heart of the crisis throughout the year was the significant gap between the demand for medical professionals and the state's ability to employ them.

The issue of unemployed healthcare graduates, particularly doctors and nurses, ignited nationwide protests, setting an unfortunate tone for the year.

The National Health Council's April announcement to recruit 1,650 new healthcare workers —including 1,200 doctors and a mere 200 nurses — was met with a mix of cautious relief and outright disappointment.

Nobuhle Makhanya, a 27-year-old unemployed doctor from KwaZulu-Natal who had been searching for a post since completing her community service, saw the move as a sign that the government was finally listening.

“It does feel like a success,” Makhanya said, reflecting on the numerous marches she had participated in. “Our demands have been heard and addressed, and we hope that talks will still be happening and that there are long-term and sustainable solutions to this issue.”

However, this optimism was quickly overshadowed by criticism from various unions and professional bodies who deemed the recruitment a ‘drop in the ocean’.

The Democratic Nursing Organisation of South Africa (Denosa) was particularly incensed, labelling the 200 nurse posts a “token gesture” and an “insult to the nursing fraternity”.

“In the face of a nationwide crisis of nurse shortages, this announcement is not only shockingly inadequate but downright insulting,” a Denosa representative stated in a strong year-end assessment.

The union pointed to vacancy rates as high as 28% in provinces like the Free State and Eastern Cape, warning that national projections suggested a shortfall of over 100,000 nurses by 2030.

The Rural Doctors Association of Southern Africa (RuDASA) echoed the sentiment, noting that the 200 new posts would not even replace the 2,000 nurses lost due to the withdrawal of overseas assistance in certain priority districts.

The lack of staff was acutely felt in KwaZulu-Natal, where facilities struggled to function effectively.

In September, Denosa’s provincial secretary, Andile Mbeje, revealed the shocking reality that nurses, already “overstretched” due to shortages, were being forced to perform non-medical duties.

“When there are no cleaners, nurses are forced to do the cleaning before attending to patients,” Mbeje disclosed, further stressing that a ward with 60 beds might be staffed by only three nurses.

Dr Phumelele Khumalo, provincial chairperson for the South African Medical Association Trade Union (Samatu), confirmed the “burning out” of doctors across the province.

She recounted her own gruelling experience as a junior medical officer: “I would be the only surgeon on the call with just two interns, and I would have to run the casualty, emergency ward, run theatre, and all the surgical wards on my own in the night.”

Further compounding the staffing crisis was the devastating shortage of specialised critical care resources, which dominated headlines in the final months of the year.

Research by Professor Fathima Paruk, highlighted in November, revealed that South Africa has a mere five ICU beds per 100,000 people, compared to Germany’s 39.

The human cost of this scarcity was brought to light by tragic individual stories. Yolanda Dyantyi mourned a 29-year-old friend whose death, she alleged, was exacerbated by a lack of ICU beds.

Another woman shared that her father waited six weeks for an ICU bed for a bypass, only for the delay to cause his gangrene to spread, resulting in him becoming a double amputee.

A Durban doctor, who spoke anonymously, painted a bleak picture of patients with life-threatening conditions often being relegated to general wards. “Poorer patients often face a lack of available beds, leading to treatment in passageways,” he stressed.

Dr Nonkululeko Boikhutso, CEO of Nelson Mandela Children's Hospital, confirmed that the lack of ICU beds meant children faced delays of “weeks or months” for life-saving heart operations.

Adding to the despair was the protracted surgical backlog. Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi confirmed in September that elective surgeries across orthopaedics, general surgery, urology, and ophthalmology were heavily delayed due to the “limited number of skilled specialists”.

Caitlyn Micholson’s story, who succumbed to metastatic melanoma after what her mother described as “prolonged” diagnostic and treatment processes at various government hospitals, became a potent symbol of the surgical delay crisis.

“The process just to get a diagnosis was so prolonged. We had to wait weeks for a scan and weeks for a biopsy,” her mother, Tamarin Nieuwoudt, lamented.

Other citizens, like Tracey Williams and Cheryl Wagner, shared years-long waits for gallbladder removal and hip replacement, respectively, with their health deteriorating in the interim.

Beyond the failures of staffing and infrastructure, the shadow of corruption loomed large. The promise of accountability for the siphoning of public funds was a rare positive note in a grim year.

Following the death of Tembisa Hospital CEO Dr Ashley Mthunzi in April last year, Motsoaledi pledged in October 2025 to pursue his estate over his alleged role in the looting of over R2 billion in irregular tenders.

“The fact that he is late does not mean that the case is over or closed,” Motsoaledi affirmed, signalling a tough stance against corrupt officials.

The minister warned that health officials implicated in wrongdoing were “dead meat” and would face the same consequences as one of the alleged syndicate leaders, whose expensive properties, including Lamborghinis, were confiscated by the Special Investigating Unit (SIU).

In summing up the turbulent year, Dr. Imran Keeka, DA spokesperson on Health, articulated the enormous challenge ahead. “With the rising burden of disease and trauma, the demand far exceeds the available capacity,” he said, calling for a phased expansion of ICU capacity, investment in staff training, and stronger retention efforts for skilled professionals.

As South Africa closes the book on 2025, the reality remains that without massive, sustained investment and decisive action to purge corruption and address systemic shortages, the public health system would continue to haemorrhage resources, staff, and, most tragically, patient lives.

karen.singh@inl.co.za