Removing medical aid tax credits could backfire on NHI funding plans

With legal challenges to the controversial National Health Insurance (NHI) Act wending their way through various courts, there continues to not only be a lack of clarity on rolling out national healthcare but also bankrolling it.

Image: Supplied

With legal challenges to the controversial National Health Insurance (NHI) Act wending their way through various courts, there continues to not only be a lack of clarity on rolling out national healthcare but also bankrolling it.

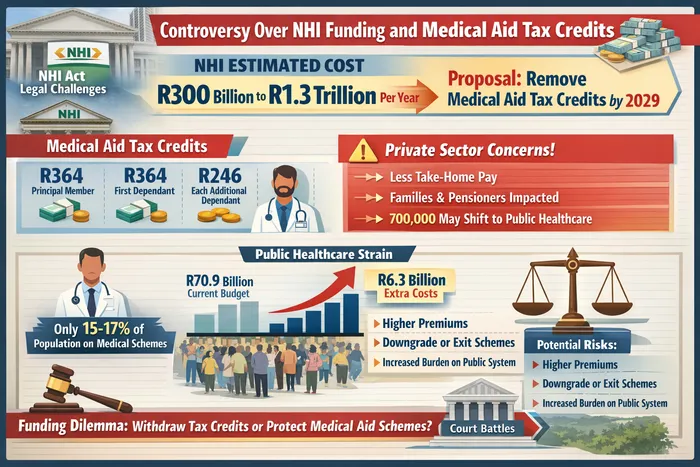

One funding suggestion by Nicholas Crisp, the deputy director-general responsible for NHI in the Department of Health, has caused substantial consternation: slowly withdrawing and then eliminating medical scheme tax credits by 2029.

Medical tax credits operate as a direct reduction in a taxpayer’s liability. Current allowances are R364 monthly for the principal member, R364 for the first dependant, and R246 for each additional dependant.

The theory is that eliminating these credits could pull in between R30 billion and R35 billion a year towards NHI funding. Universal healthcare is expected to cost anywhere from R300 billion to R1.3 trillion annually, depending on the level of care.

However, industry experts say the minister’s confidence is misplaced, and that withdrawing tax credits would harm both the funding goal and the healthcare system.

The numbers don’t add up

Garth Zietsman, Freedom Foundation analyst, has run the figures and found a critical flaw. If credits are eliminated, as many as 700 000 lower income medical scheme members could be forced to rely on public health.

This will cost the state as much as R6.3 billion yearly to treat people who were medical aid members, dropping the net benefit to around R27.7 billion.

“Private health care and medical aids relieve the state of the burden. Instead of eliminating tax credits, they should be extended to all forms of health spending,” says Zietsman.

The Board of Healthcare Funders (BHF) has already expressed concern at Crisp’s proposal. MD Dr Katlego Mothudi says such a policy decision would have “profound public interest implications”.

The National Health Insurance and medical aid tax credits controversy by the numbers.

Image: ChatGPT

Who bears the cost

Fikile Matabane, executive of Employee Benefits at ASI Financial Services, explains that removing these credits means less take-home pay for tax-paying South Africans.

“For many families, this would feel like a tax increase when the cost of living is already high. Middle- and lower-income earners, pensioners, and families with dependants who rely on the credit to manage healthcare costs would be most affected,” says Matabane.

Dr Katlego Mothudi, MD of the Board of Healthcare Funders (BHF), notes that “nearly 67% of medical scheme members come from previously disadvantaged communities. These are not the wealthy elite, they are teachers, nurses, security guards, and office workers doing their best to fund their own healthcare.”

Removing tax credits “would make medical aid more expensive, likely leading members to downgrade plans, remove dependants, or exit schemes altogether,” says Matabane.

Older risk pools

Another issue Matabane raises is that medical aid in South Africa is already expensive and out of reach for most people, with only about 15 to 17% of the population belonging to a medical scheme, often because it is offered or subsidised by employers.

Because younger and healthier members are the most price-sensitive, they are the most likely to leave. “As they exit, schemes are left with smaller, older risk pools, which increases average claims costs and drives premiums higher,” Matabane says.

Inadvertently, says Matabane, this would place additional pressure on the public healthcare system, potentially before NHI services are fully established.

“Medical aid tax credits currently play a stabilising role by supporting private healthcare participation and easing pressure on the public system. Removing them too early, without clear improvements in public healthcare capacity, risks weakening both systems simultaneously,” says Matabane.

Won’t force exodus

Minister of Health Aaron Motsoaledi said that removing tax credits is catered for in the Act.

Motsoaledi said as recently as a month ago that removing medical aid tax credits would not force anyone to leave their private medical schemes.

The minister added that scheme members would continue choosing between private and public healthcare providers, and that redirecting funds from tax credits could strengthen public healthcare for most South Africans.

The strained public system

About 86% of South Africa’s population relies on state-provisioned health care, with the annual budget for this service at R70.9 billion as of the 2025/26 tax year.

Of the current budget, Motsoaledi said during his department’s budget speech in July last year, R1.7 billion will go towards hiring 1 200 doctors, 200 nurses, and 250 other health professionals, while beds and mattresses, among other articles of furniture, will cost R1.3 billion.

Permanently hiring 27 000 community health workers will add another R1.4 billion to the expenditure line.

According to World Bank and World Health Organization data, South Africa had about 0.81 physicians per 1,000 people in 2021, up slightly from earlier years. This measure, the latest available, includes both public and private doctors.

In presenting his budget, Motsoaledi said he aimed “to lay a strong foundation in preparation for improvement of the public health system of our country, to lay the ground for the NHI”.

Phase 2 of the NHI programme, which includes establishing the NHI Fund and commencing service purchases, is scheduled to begin in 2026, according to the Trialogue Knowledge Hub.

Yet, the Western Cape government’s legal challenge in the Constitutional Court cited insufficient public participation. There are also multiple High Court cases by medical schemes, industry bodies, and business groups that would need to be resolved before there is any clarity on implementation timelines or funding mechanisms.

PERSONAL FINANCE