Crisis of Credibility: SAPS, Madlanga Commission expose deep-rooted corruption

Commission of Inquiry

Across townships, suburbs and rural communities, reaction to the exposure of the widescale decay within SAPS has been almost the same: not shock, but exhaustion and fatigue. For many, these scandals have become a grim ritual in a democracy that promised integrity but has delivered repetition.

Image: Sora/AI

South Africans are watching yet another wave of corruption revelations — from Lieutenant General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi’s explosive claims about criminal infiltration in the police, to testimony before Parliament’s ad hoc committee and the Madlanga Commission — with weary eyes.

Across townships, suburbs and rural communities, the reaction is the same: not shock, but exhaustion and fatigue. For many, these scandals have become a grim ritual in a democracy that promised integrity but has delivered repetition.

“We are fatigued by repetition”

Siyabulela Jentile, president of #NotInMyName

What the country is witnessing, according to Jentile, “isn’t new — it’s the continuation of a long, painful story of institutional betrayal.”

“South Africans are not numb by choice; we are fatigued by repetition. Each revelation of corruption lands on ground already scorched by previous scandals — from state capture to failures in local governance. When accountability becomes the exception rather than the norm, outrage slowly turns into resignation.”

Public trust in the South African Police Service (SAPS), he said, has been profoundly eroded.

“People no longer see the police as protectors but as an extension of a state that has lost moral authority. In townships and rural areas, residents feel safer calling community patrols or neighbourhood-watch groups than reporting crimes to SAPS.”

The consequences, Jentile warned, are devastating.

“A compromised police service doesn’t just fail to solve crimes; it incubates criminality. It gives organised syndicates, drug networks, and corrupt officers room to operate with impunity. It means gender-based violence cases go uninvestigated, children disappear without trace, and communities resort to vigilantism.”

For Jentile, corruption has “festered into our national fabric.”

“We joke about it, anticipate it, even budget for it. That’s the danger: when wrongdoing becomes predictable, accountability becomes optional. But the fact that people are no longer shocked is not a sign of acceptance — it’s a symptom of exhaustion. Civil society must help rebuild that moral outrage and turn it into organised demand for reform.”

“A nation of spectators to its own crisis”

Melusi Ncala, Senior Researcher at Corruption Watch

“It’s tragic. It is deeply worrying because it shakes the foundations of a democratic society,” said Ncala. “The police service is an institution we all have to interact with — from getting documents certified to opening criminal cases. When that institution is broken, democracy itself is weakened.”

He believes the apathy visible in society today stems from a cycle of empty promises.

“We’ve had ministers, commissioners, and task teams promising clean-ups year after year, yet crime and corruption persist. Community members report drug dens and instead get threatened by the very officers meant to protect them. The problem is not new — we’ve been raising it for years.”

Ncala said even the political response to the latest scandals feels recycled.

“The president sets up commissions; Parliament forms ad hoc committees. But when you look closely, these platforms are often used for point-scoring, even gossip. We saw that with the ad hoc committee hearings — entertainment value instead of accountability.”

"When you look at the spectacle, for example, in Parliament, even though some influencers outside Parliament would tell you it was quite engaging with Lieutenant General Mkhwanazi, but we need to compare it with what the terms of reference for the Ad Hoc Committee are. When you do that, you realise that these politicians were really engaging in gossip or political issues as opposed to really delving into issues that really, really matter, issues with significance to the outcome of the ad hoc committee of Parliament," said Ncala.

"At the end of the day, the ad hoc committee needs to compile a report, and questions need to be asked that will address several issues. The main thing is the veracity of the claims made. This is not an opportunity for members of Parliament to say, did you really see the leader of my political party at a club. That is not what the purpose is, that speaks to the entertainment value. That is what these politicians are doing, they are obfuscating yet again."

He warned that society has begun to watch corruption like a TV show rather than confronting it.

“It’s almost as if we’re spectators, not participants. People are thinking, ‘this too shall pass.’ But the more we treat corruption as spectacle, the less pressure we put on those in power to change it.”

KZN police commissioner Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi during his testimony before the ad hoc committee.

Image: Henk Kruger / Independent Newspapers

“Communities now see police as criminals”

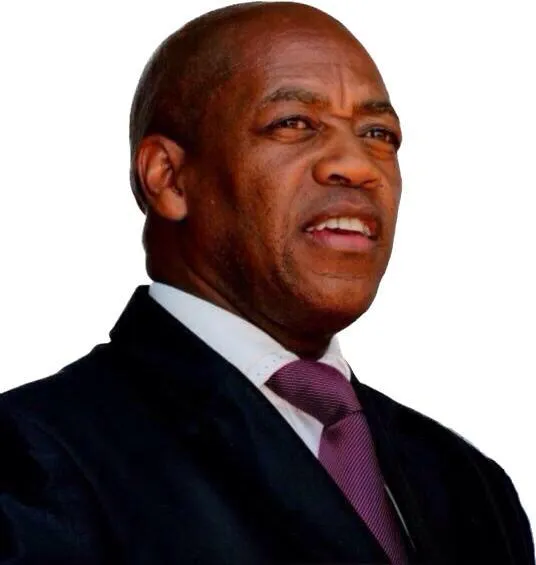

Andy Mashaile, retired Interpol ambassador and security strategist

“The erosion of trust means people have given up on anything to do with the police,” said Mashaile.

“Communities now look at the police as criminals. Anything involving SAPS is a no-brainer — they simply expect failure or corruption.”

He described South Africans as “numb from the sores.”

“Even when something drastic happens, it takes a long time to feel it. People do not trust the police, hence you find even a serving lieutenant general being suspected of working with criminals,” he said.

Renowned security strategist Andy Mashaile, a retired Interpol ambassador, spoke to IOL

Image: Supplied

For many citizens, watching senior officers like Lieutenant General Shadrack Sibiya being grilled in Parliament is less about justice than curiosity.

“People are not expecting reform — they are just hoping someone goes to jail,” Mashaile said. “They have lost faith that these inquiries lead to change.”

He warned that the breakdown in trust could have lethal consequences.

“We’ve seen revenge killings in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal, and mob justice in Limpopo. When people stop trusting the justice system, they take the law into their own hands. The result is a collapse not only of policing but of belief in justice itself — a corrosion that spreads across our society and even across the SADC region.”

Deputy national commissioner of police Shadrack Sibiya denies ever being labeled a rogue officer, rejecting claims made by General Masemola during Parliament’s ad hoc committee hearing.

Image: Armand Hough / Independent Newspapers

A pattern too familiar

From the Madlanga Commission’s testimony on institutional capture to Mkhwanazi’s startling allegations of criminal networks inside SAPS and Parliament’s ad hoc committee’s public hearings, one pattern emerges: deep-rooted corruption in the very institutions meant to protect South Africans.

The narrative is disturbingly familiar. It stretches from the Zondo Commission of Inquiry to countless internal SAPS scandals, where suspended generals quietly resurface or face endless disciplinary delays.

Analysts say the real story now is not just corruption itself but how ordinary people have emotionally adapted to it. The nation’s outrage fatigue reflects years of promises unkept and inquiries unresolved.

National police commissioner, General Fannie Masemola testifies before parliament's ad hoc committee investigating allegations of corruption and interference in the criminal justice system.

Image: Henk Kruger/Independent Media

Community policing forums: collapsing partnerships

Some Community Policing Forums (CPFs) in Gauteng, Limpopo, and Mpumalanga say cooperation with local police has collapsed. Many CPF leaders report intimidation when exposing corruption inside stations.

A CPF chairperson in Gauteng told IOL: “We applaud the exposure, but the next day, our members still don’t feel safer.”

In rural Limpopo and informal settlements outside Cape Town, residents say crime reporting is often pointless — suspects are tipped off or cases disappear. The erosion of trust has turned partnership into a parallel existence: communities fend for themselves while police credibility decays.

The data behind distrust

The Afrobarometer 2024 study found that six in ten South Africans believe “most or all police officers are corrupt,” while only one-third say they trust the police.

The Institute for Security Studies (ISS) reports a sharp decline in public confidence over the past decade, driven by perceptions of collusion with criminals and political interference.

The HSRC Social Attitudes Survey adds that trust levels in the police are now at their lowest since 1994 — even as fear of crime continues to rise.

These numbers confirm what citizens already feel: the social contract between state and citizen is fraying.

Consequences of broken trust

A collapsing relationship between communities and law enforcement is already reshaping public life:

Under-reporting of crime: Victims turn to private security or remain silent.

Vigilantism: Mob justice and revenge killings are rising.

Unequal safety: Wealthier areas buy protection; poorer ones are left exposed.

Disillusioned officers: Honest cops are demoralised by association.

The result is a feedback loop of insecurity — where fear breeds corruption, and corruption breeds more fear.

Civil society’s call for renewal

Groups such as Corruption Watch and #NotInMyName are demanding a shift from commissions to consequences — prosecutions, independent oversight, and protection for whistle-blowers.

Police unions POPCRU and SAPU have often defended honest officers while acknowledging that corruption within SAPS “is a cancer that must be confronted.”

President Cyril Ramaphosa has vowed that findings from the Madlanga Commission will guide sweeping reforms, but citizens have heard similar promises before.

President Cyril Ramaphosa addressing the nation during a "family meeting"

Image: Jairus Mmutle/GCIS

A society exhausted, not indifferent

From civic activists to security experts, every voice converges on the same truth: South Africans are not indifferent — they are exhausted.

As Jentile put it, “Our democracy is not collapsing; it is calling for renewal.” That renewal, he said, begins when honesty becomes as courageous as protest once was.

Whether the Madlanga Commission, Mkhwanazi’s revelations, or Parliament’s inquiries will deliver that renewal remains uncertain.

But one reality is undeniable: When corruption no longer shocks us, it has already conquered more than our institutions — it has conquered our expectations.

jonisayi.maromo@iol.co.za

IOL News