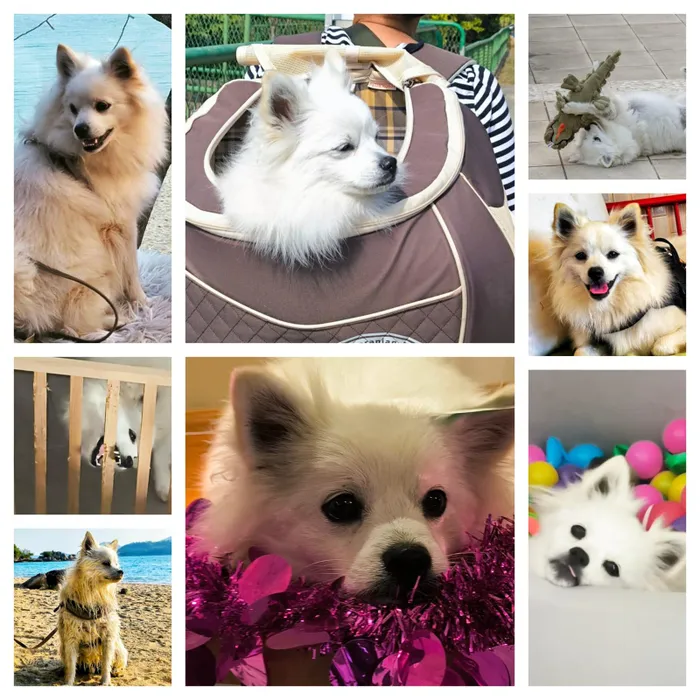

Leo is a cross between a Pekingese, a Pomeranian and a Japanese Spitz — plus several generous dollops of attitude and trouble. He’s a dog who has learned what it takes to have everything his own way, and then refined the art of being in charge.

Image: Lance Fredericks / DFA

LEO’S nickname is “Little Monster”, and it fits. Leo has been meticulously imposing his reign of terror on family, friends, strangers, birds and dogs in the little village where he lives.

Here’s the thing: Leo is a cross between a Pekingese, a Pomeranian and a Japanese Spitz — plus several generous dollops of attitude and trouble. He’s a dog who has learned what it takes to have everything his own way, and then refined the art of being in charge.

The Pekingese in him brings confidence and that regal, sometimes stubborn, demeanour. The Pomeranian adds intelligence, boldness and a lively spark. And running through Leo’s veins, tattooed in his DNA, is the Japanese Spitz — active, playful, confident, but requiring consistent training and early socialisation because of that bold streak.

If you haven’t figured it out yet, let me spell it out: Leo, though sweet and adorable, is lively, energetic and very, very naughty. I have come to associate Hong Kong with the sound: “Leo! No! Don’t be naughty!”

He’s a fluffy white ball of chaos, and his family have had to adapt. They have learned to shape their reality around the hairy havoc who lives by his own rules. Being wise, they’ve figured out how to control him by making him believe he’s in control.

When Leo sees the ocean — winter, summer or typhoon — he charges into the surf. The problem is that he then has to be washed, dried and groomed. So the solution is simple: keep him on a leash at the beach.

He also goes off the rails on walks. He snaps at other dogs — not viciously, but unpredictably. He sometimes flops down and refuses to move. And he marks every bush and pole along the route with his little “pee-pistol”. If you want a “quick” walk with Leo, you don’t walk him. You put him in a trolley. He loves it, and behaves himself when pushed around like royalty.

Think he’s spoiled? I’m not done.

Leo refuses to eat his kibble from a dish. His nanny has to toss the pellets to him, feeding him like a chicken. Then he catches and scoffs them down with relish.

There’s more I could complain about, but I think you get the picture.

Here’s the weird thing: when I return to South Africa, I am going to miss Leo. In a strange way, he has conditioned me to accept and embrace his quirks and eccentricity. I will miss him precisely because he is such a bold, confident, arrogant — yet affectionate — gemors.

But it’s not only Leo that will make me miss Hong Kong’s Island Districts. When I head back to Mzansi, I am going to miss the sensation of feeling safe.

There were days here when we went to the market, or went to bed, forgetting to lock the doors. The property’s gate was never locked. In the small village where I resided, people — young and old — tend their gardens and beautify their homes without first investing in high walls, spiked or electrified barriers, or armed security.

Community social media groups post alerts about lost or stray animals or reptile sightings. There is no constant nagging fear of being robbed, attacked, assaulted or worse.

In this part of the world, you see, laws are clearly defined. And above all, laws are enforced.

There are penalties for driving while using a mobile phone, for not wearing a seatbelt, for littering, for smoking in prohibited areas. Yes, just like in South Africa, you might say. But here’s the subtle difference: here in the Far East, lawbreakers pay the price for their transgressions.

In Hong Kong, the standard fixed penalty for littering in a public place is HK$3,000 (R6,087). For more serious illegal dumping, you could find yourself HK$6,000 (R12,124) out of pocket.

In short, there are consequences for bad behaviour. Offenders are not punished because authorities dislike them; they are punished because the laws are enforced. The result is a society that feels more orderly. It’s simply a matter of when transgressions are not tolerated, fewer people transgress.

When I think about going back home, I already feel the burden of reactivating constant vigilance. I have to remember to look over my shoulder. Not find myself alone in deserted places. Lock the car door. Secure the house. Check the gate. Do a recon of the yard before bedtime.

It’s back to keeping tabs on community crime alerts — and that’s before we even get to the so-called “minor” irritations of litter, public urination, poor service delivery and inattentive drivers.

Don’t get me wrong. I love South Africa. But hear me when I say that I have not been enjoying how home has been making me feel for quite a while now.

In the parts of the Far East I have visited, criminals are the ones watching their backs. They are careful, wary of stepping out of line and facing consequences. In South Africa, law-abiding people are warned not to buy certain cars that feature as highly hijackable, told to avoid deserted places, and advised to beef up their home security.

One day last week, as Leo bolted out of the front door with my cap in his mouth — fully intending to rip it to shreds under the shade of his favourite lemon tree — the lesson crystallised.

Firstly, we cannot expect people to have respect for law and order until we teach respect to those we have entrusted to enforce those laws. Secondly, when you have people accepting that breaking the law is somehow normal, the whole society suffers.

But I think Pierre Trudeau sums it up beautifully when he says: “I think we should be prepared to pay the consequences of breaking the law and that is either paying the penalty for it, or leaving the country.”