Drought is exposing world relics - from dinosaur tracks to Nazi ships

Wreckage of a World War II German warship is seen in the Danube in Prahovo, Serbia. Picture: Reuters/Fedja Grulovic

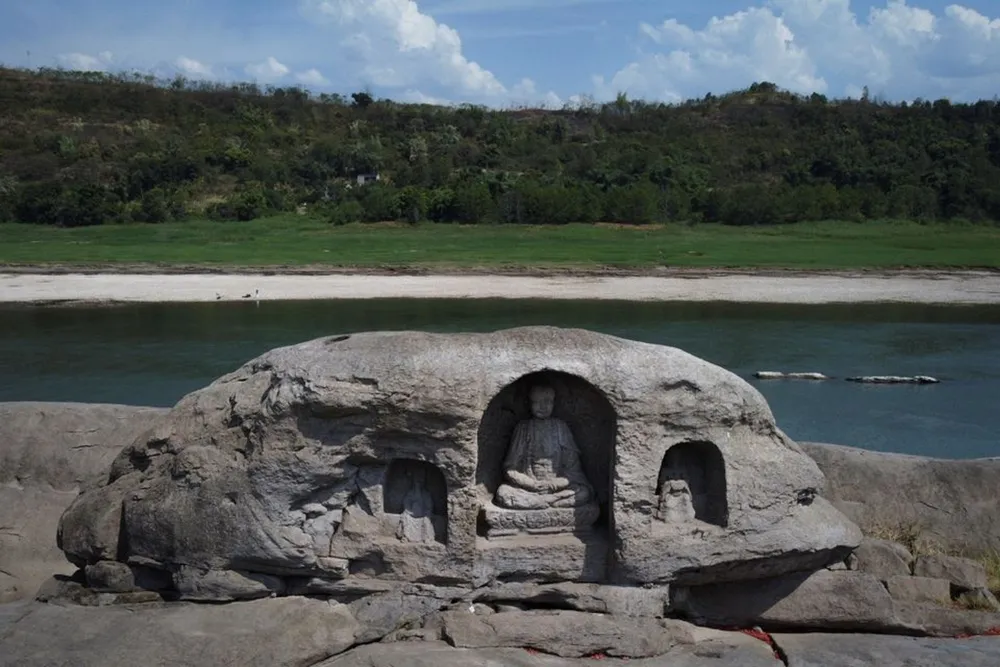

PREVIOUSLY unseen dinosaur tracks dot a dried-up riverbed in Central Texas. Sunken warships poke out from port waters on the Serbia-Romania border. Once-submerged Buddhist statues loom above the Yangtze River banks in Chongqing, China.

As record-breaking drought - fuelled by human-caused climate change - parches waterways around the world, hidden relics that would have been difficult or impossible to access in milder years are emerging from below the surface.

The discoveries are a world history windfall, offering a rare peek at lost pieces of humanity's past and ancient life on Earth.

But their exposure sets off a race against time for researchers, who have only a short window to study them before the rivers roll back.

"We're amazed at how rapidly things emerge and then disappear in the blink of an eye," said Vincent Santucci, senior paleontologist at the National Park Service, who has excavated fossils from eroding cliffs and shorelines. "When we have low water levels, there are a lot of things that are exposed that we haven't seen in our lifetime and may have never been documented. We rush to preserve those."

At Dinosaur Valley State Park in Glen Rose, Texas, weeks of blazing heat have wrung the Paluxy River dry, revealing multiple sets of dinosaur footprints that experts say date back 113 million years.

Some came from a creature called Acrocanthosaurus, a three-toed, bipedal carnivore that looked like a slightly smaller Tyrannosaurus rex, according to Stephanie Garcia, a spokesperson for the park. As an adult, it would have stood about 15 feet tall and weighed about seven tons. Another set of footprints came from a four-legged, long-necked herbivore called Sauroposeidon that stood a towering 60 feet tall and weighed about 44 tons.

While dinosaur tracks themselves aren't particularly rare, they're important to researchers because they provide clues about how the animals lived.

"The tracks were made along an ancient, inland sea during the Cretaceous period," Garcia told The Washington Post. "The dinosaurs stepped in thick mud that held their track shapes well with a lot of the detail."

With rain in upcoming forecasts, Garcia said the tracks will soon be covered again. Workers have cleaned, mapped, measured and photographed tracks to monitor changes over time. The park is also mulling other solutions that would allow the tracks to survive longer if they're exposed again, according to Garcia.

"However," she added, "nothing the park can do can stop the forces of weathering and erosion forever."

Repeated cycles of exposure and covering up can wear on fossils that would otherwise be protected by silt and sediment. Water flooding back into a dry area can erode rock and shoreline. Loose debris could bury or damage fragile specimens. Other fossils are at risk of being washed out by the advancing current. Intense storms pose similar dangers.

These threats are accelerating as climate change worsens, adding pressure on scientists and field workers to protect their finds before they're destroyed or swept away, said Santucci, of the National Park Service.

"Given the wild fluctuations in weather and precipitation, we can have these long dry periods exposing things and then catastrophic flooding," he said. "The high-energy nature of those floods can completely wipe out a fossil site."

In special cases, Santucci said, specimens are collected for safe keeping. More often, scientists inventory what they find, draw maps, take photographs, even draw up 3D models. Then they develop a plan for periodically monitoring the site to see what changes over time. Ultimately, Santucci said, they're at nature's mercy.

"We have to come up with schedules to get out there really quickly," he said, "before they wind up lost forever."

In the rapidly drying Danube, Europe's second-longest river, researchers investigating a graveyard of Nazi warships exposed by record-low waters may face similar problems.

The World War II-era vessels uncovered near the Serbian port town of Prahovo in August were part of a German Black Sea fleet that sank in 1944 while retreating from Soviet forces. More than 20 have appeared so far, and others are expected to be uncovered along the banks.

It's a treasure trove for maritime scholars and military historians. But it's also riddled with hazards: Serbian officials say there may be thousands of rounds of ammunition and other undetonated explosives inside.

Even if researchers can safely reach the ships, they'll face a time crunch. In the short term, waters will return, reclaiming the sunken vehicles. In the longer term, rising and falling water levels driven by intensifying drought exposes the metal structures to sunlight, rust-inducing oxygen and potentially volatile river conditions, all of which could affect their longevity.

"Any time we introduce any natural or cultural interference, we're talking about degradation and thinking about how long those sites are going to be around," said Jennifer McKinnon, a maritime archaeologist at East Carolina University.

"The flip side is that them being uncovered is an excellent opportunity for outreach, for the global community to understand history and see what only divers might have been able to see," she said. "There's going to be some destruction, but you also understand the importance of that public exposure."

While the Danube is revealing mankind's destructive side, other waterways have in recent months revealed a host of exhibitions in creativity.

Buddhist statues built during the Ming and Qing dynasties cropped up on an island reef in the Yangtze, which is experiencing record-low water levels. In Spain, archaeologists were recently able to access an ancient monument known as "Spanish Stonehenge" in a Tagus River reservoir; it has seldom been visible since the area was flooded in the 1960s to build a dam. And in Iraq, the remains of 3,400-year-old city came into view in June, when drought sapped waters in a reservoir in the country's north.

The fleeting view of these treasures comes at an enormous ecological cost. Drought ravages crops, strains livestock and native species. It worsens air quality and raises the risk of wildfires, among other environmental ills. As the planet warms, these cycles are all but certain to continue.

"We can look at it as a two-edged sword," Santucci said. "We can document the adverse impacts of climate change but benefit from finding things that have been exposed due to the same factors."

- THE WASHINGTON POST