Rift Valley Fever confirmed in Northern Cape - Farmers urged to act swiftly

Rift Valley Fever outbreak has been confirmed in Northern Cape, and farmers are urged to vaccinate livestock immediately and boost biosecurity as heavy rains fuel mosquito spread.

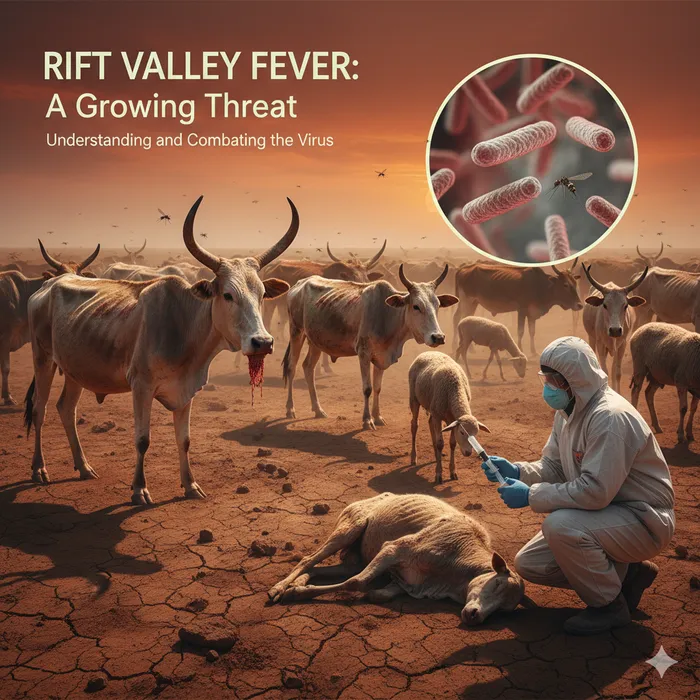

Image: Gemini

SOUTH African livestock farmers in the Northern Cape are on high alert following the confirmation of a Rift Valley Fever (RVF) outbreak in the Kakamas area near Augrabies Falls. The Northern Cape Department of Agriculture, Environmental Affairs, Rural Development, and Land Reform has issued an urgent health warning, emphasising the need for immediate vaccination and enhanced biosecurity measures to prevent a wider spread.

The outbreak was detected after blood samples from a sheep herd tested positive for the RVF virus, a mosquito-borne pathogen that thrives in wet conditions. Symptoms in affected animals include bloody diarrhoea, nasal bleeding, sudden abortions, high fever, and unexplained deaths, particularly devastating in young lambs and kids, where mortality rates can exceed 90%.

"This is a highly contagious virus that can also transmit to humans," said Yolande Botha, operational officer for the Red Meat Producers’ Organisation (RPO) in the Northern Cape. "Farmers must not handle suspected animals themselves; contact your nearest state veterinarian immediately."

The warning comes amid favourable conditions for mosquito proliferation, with recent rainfall across the province and forecasts predicting more wet weather. Brand du Toit, chairperson of the RPO in the Northern Cape, noted that the organisation had been proactively warning producers about the risk in recent months. "RVF has major economic consequences for the red meat industry," he added. "With more rain on the way, the probability of a larger outbreak is high -vaccination is our best defence."

Recommended biosecurity measures

Authorities are strongly advising farmers to:

- Vaccinate all sheep, goats, and cattle against RVF without delay. Onderstepoort Biological Products has been contacted to ensure vaccine availability on an urgent basis.

- Wear full personal protective equipment (PPE) when dealing with sick animals, births, or abortions.

- Safely dispose of aborted fetuses and placentas through deep burial or incineration.

- Eliminate mosquito breeding sites by draining standing water and applying repellents or vector control methods.

- Report any suspicious symptoms, such as abortion storms or unusual livestock deaths, to state veterinary services immediately.

Human infections typically occur through direct contact with infected animal tissues, blood, or fluids, rather than mosquito bites in most cases. Symptoms in people range from mild flu-like illness (fever, muscle pain, headaches) to severe complications, including vision loss or hemorrhagic fever in rare instances.

Broader context in 2025

This is not an isolated incident for South Africa this year. Reports indicate RVF cases in sheep were first noted as early as May 2025, with diagnoses confirmed in the Augrabies region and potential spread to other provinces. The virus, first identified in Kenya in 1931, causes periodic outbreaks linked to heavy rains and flooding, which boost mosquito populations.

While no human cases have been publicly reported in connection with the current Northern Cape outbreak as of mid-November 2025, the zoonotic nature of RVF underscores the risk to farm workers, veterinarians, and abattoir staff. Globally, RVF remains a concern: In West Africa, a separate outbreak in Mauritania and Senegal has claimed over 40 lives since September 2025, highlighting the virus's potential lethality.

South Africa's agricultural sector, a key contributor to food security and exports, cannot afford complacency. Past major epidemics in 1950-1951, 1974-1976, and 2010-2011 devastated livestock herds and led to human fatalities. Early intervention through vaccination and reporting has proven effective in containing smaller outbreaks like this one.

Farmers outside the immediate area, particularly in rain-affected regions, are encouraged to review their biosecurity protocols. As climate patterns shift and extreme weather events become more frequent, proactive measures against vector-borne diseases like RVF will be crucial for the industry's resilience.

For the latest updates, producers should contact their local state veterinary office or the Red Meat Producers’ Organisation. Swift action now could prevent a repeat of history's costly lessons.

Related Topics: