The sparkle and the spill: Why Kimberley’s brand story is at war with reality

OPINION

The Kimberley skyline above the Big Hole — the government’s social media post called it “a sparkling city where history meets heart.” Residents had other words.

Image: South African Government Facebook page

By Monty Quill

THERE’S a lovely post doing the rounds courtesy of the South African government on Facebook – a sun-dappled ode to Kimberley, “where history meets heart” and every sunrise promises a new chapter. It’s the kind of copy that looks terrific on a tourism brochure – a wide shot of the Big Hole framed by a hopeful sky, the city gleaming just beyond the cliff’s edge. The problem is that most residents read it and thought: Which Kimberley is that, exactly? Because the one we’re living in keeps cutting the water, coughing sewage into streets, and charging us more for the privilege.

This is the distance between message and pavement – the glittering brand and the sludge in your gutter. It isn’t just a bad look; it’s a trust problem. People can handle hard truths; they cannot abide being told that the odour is character.

Kimberley is, indisputably, a city of world-class heritage. It also, at present, suffers from world-class leaks. Our water system loses so much treated supply that one wonders whether the pipes are in open rebellion. When the taps do work, they sometimes splutter like a startled meerkat; when they don’t, entire neighbourhoods embark on an impromptu fitness programme lugging buckets. We’re asked to be patient while “bulk upgrades” are being designed, costed, consulted, and possibly dreamed about. In the meantime, residents have perfected the art of the survival timetable – shower when there’s a trickle, do laundry if the pressure holds, and boil whatever the taps surrender.

Sewage, that most democratic of substances, has been making uninvited house calls. It seeps through manholes, grazes past schools, and forms surprise wetlands where no birder would bravely tread. The city’s response often arrives as a photo opportunity: a vacuum truck, a promise, and the recurring plot twist of “temporary relief”. You can only mop your passage so many times before the word “sparkle” develops an edge.

Electricity is the other great paradox. On paper, the smart meter roll-out is a step towards a modern grid. In practice, many households hear the word “smart” and translate it as “expensive”. Tariffs rise, capacity charges lurk, and the explanation is always that cost recovery is essential to keep the lights on. Fair enough. But cost recovery without service recovery feels like paying premium rates for phantom services. No one enjoys paying top tariff to watch their freezers defrost during a midweek sag in voltage. Businesses quietly factor in generator fuel as a line item; households learn the language of kilowatt hours the way past generations learned their times tables.

Roads? Let’s agree that Kimberley is pioneering a new urban sport: rally driving at 40km/h. The city fills holes; the rains and trucks unfill them. Repeat. It’s hard to attract visitors when the recommended route from one landmark to another includes the advice, “aim for the least menacing crater and pray”. The phrase “maintenance backlog” is technically accurate and emotionally anaesthetised. What residents see is ambulances dodging hazards and tyre shops with suspiciously buoyant turnovers.

Then there’s governance – the polite umbrella under which we hide the weather of everything else. There is a sense, not limited to cynics, that our municipality attempts to budget its way out of physics. Pipes don’t care about press statements. Pumps cannot be briefed into performance. You either fund repairs and competent maintenance, or you fund emergency call-outs and court cases. Either way, you pay. The difference is whether you also get dignity.

To local government’s credit, officials do sometimes venture beyond platitudes. They remind us that the system was built for far fewer people, that historic neglect created today’s bottlenecks, and that billions of rand are being marshalled for upgrades. All true. But telling a resident standing ankle-deep in a preventable overflow that “Rome wasn’t built in a day” is less a comfort than an admission. Rome, for what it’s worth, also had working aqueducts.

Show us the wattage

Meanwhile, the public mood has curdled from weary to organised. Community groups, business forums and ratepayers have marched, memo’d, and threatened shutdowns. Some councillors call this “destabilising”; most residents call it “Tuesday”. Civil action isn’t a hobby in Kimberley – it’s become the operating system. People want measurable things: a pump station that stays alive for longer than a weekend; a road repaired once and properly; a billing system that is both accurate and humane. None of this is utopian. It is the minimum viable standard for a functioning city.

So, what to do with the Facebook fairy-tale? We could ignore it and get back to bucketing. We could rage into the void. Or we could treat it as an accidental invitation: if you’re going to say Kimberley “still shines”, show us the wattage. Publish monthly dashboards – leaks fixed, pipes replaced, pump uptime, tarred kilometres, outage minutes per ward, and indigent households assisted. Commit to service-level agreements that survive contact with reality. Tie executive salary increases to things residents can actually see and feel: clean streets, steady water pressure, fewer power cuts, quieter manholes. When the city fails, say so in public, quickly, with a date by which it will not fail again.

And while we’re being practical: stop announcing silver bullets. They don’t exist. Smart meters won’t solve theft if transformers blow like party balloons. New pipes won’t matter if treatment works collapse. A pothole blitz is theatre without stormwater planning and weight controls. Complex systems require sequences, not stunts. Do the boring, unphotogenic bits first; celebrate afterwards.

Kimberley will always be a story town: of firsts, fortunes and fierce people who make a plan. But it is also a town of bills and boots. The gulf between “sparkle” and street will close when residents can walk to the shop without rehearsing a route around effluent, when businesses can open without a roulette wheel of voltage, and when brides don’t budget for a tanker. On that day, the emojis will write themselves.

Until then, please spare us the perfume – we’re still elbow-deep in the mess.

* The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the DFA or its staff. While we strive to provide a platform for diverse perspectives, the content remains the sole responsibility of the contributor.

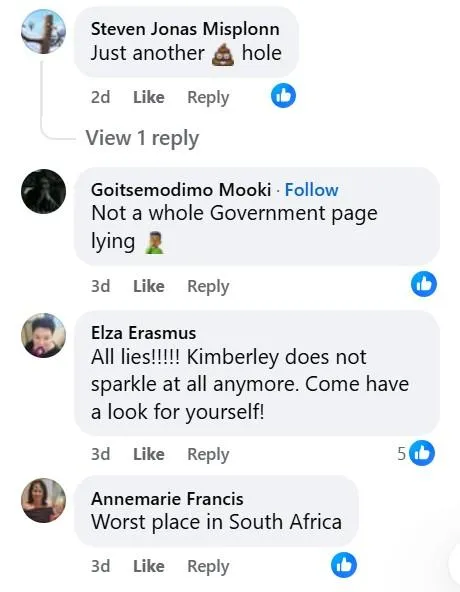

The South African government’s Facebook post portraying Kimberley as “a sparkling city where history meets heart”.

Image: South African Government Facebook page

The government’s “sparkling city” post lit up Facebook — but not in the way it hoped. Locals called it “lies,” “the worst place in South Africa,” and proof that “a whole Government page is lying.”

Image: South African Government Facebook page