Citizen science could hold the key to solving South Africa’s water crisis

South Africa’s water crisis, worsened by ageing infrastructure, leaks, pollution, and poor monitoring, was the focus of the recent Citizen Science Water Symposium hosted by IIE MSA.

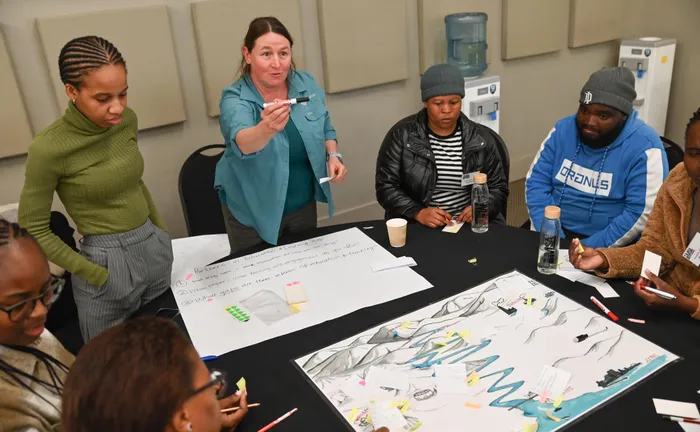

Image: Supplied

South Africa’s water crisis is deepening, with millions of citizens facing daily challenges to access safe, clean water. Ageing infrastructure, pollution, climate variability, and inconsistent monitoring continue to place immense pressure on the country’s already fragile water systems. Experts believe that empowering ordinary citizens to take part in water monitoring may be one of the most effective solutions.

This was the central message at the recent Citizen Science Water Symposium, hosted by The Independent Institute of Education’s (IIE) MSA, where researchers, government officials, NGOs and educators came together to discuss new ways to protect the nation’s water resources.

Linda Downsborough, Head of Environmental Science at IIE MSA, highlighted the importance of equipping communities with practical skills.

“Equipping citizens with the knowledge and tools to collect water quality data can help bridge information gaps and inform faster interventions,” she explained. “Our goal is to capacitate communities to recognise and respond to threats of water safety and to transform them from passive recipients of information into active participants in safeguarding their water resources.”

The urgency of this call is evident. According to the Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa loses almost half of its potable water through leaks and inefficiencies. Over three million citizens still lack basic access to water, and nearly one in five have no access to safely managed sanitation. Rural residents are the hardest hit, with only 36.7% enjoying safely managed water services, compared to 71.8% in urban areas.

One of the key challenges discussed at the symposium is the lack of standardised testing protocols for community-led initiatives. Citizen monitoring often relies on testing strips and sampling methods of varying quality, leading to inconsistent results. Delegates agreed that developing affordable, user-friendly testing kits, usable regardless of education level or language, should be a national priority.

Vanessa Stippel, lecturer in Environmental Science at IIE MSA, shared insights into the institution’s Water Quality Monitoring Initiative, which gives students hands-on experience with tools like miniSASS to assess river health.

“When participants are invested, they are more likely to share knowledge within their communities, creating a multiplier effect,” Stippel said. “This initiative enhances students' understanding of environmental science but also fosters a sense of responsibility and advocacy for water conservation in their communities.”

Government representatives also stressed the need for a centralised national database to integrate citizen-collected data. At present, much of the information gathered at the community level is not included in official reporting, slowing responses to urgent threats like cholera outbreaks.

Adding to this, Bonani Madikizela of the Water Research Commission emphasised that citizen science could also tackle unemployment by training young people in monitoring, data interpretation, and environmental project management.

“Education and skills transformation are key to preparing the next generation to solve real-world problems,” Madikizela said.

The symposium concluded with a strong message: with targeted investment in training, tools and data integration, citizen science has the potential to become a cornerstone of water management in South Africa, turning everyday citizens into frontline protectors of one of the nation’s most critical resources.

Related Topics: