The sound of a foot thumping ball, racquet whacking ball, the shouts of the players, the referee’s whistle – all were an echo. All the thumps, whacks, shots and whistles were greeted by silence.

CAPE TOWN – The sound of a foot thumping ball, racquet whacking ball, the shouts of the players, the referee’s whistle – all were an echo. All the thumps, whacks, shots and whistles were greeted by silence.

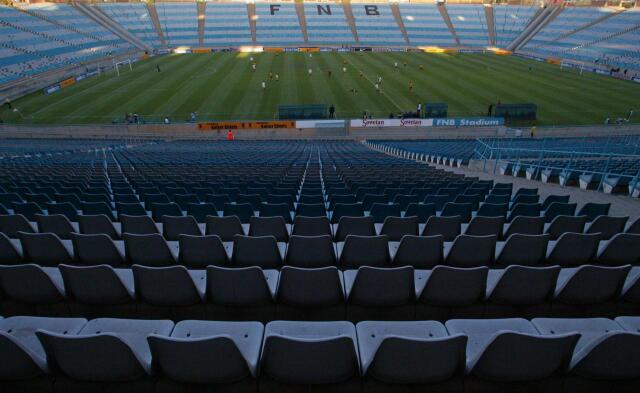

The fields and courts, the great theatres of sport, fell silent for about four months from March in 2020.

The gladiators – once they were allowed back and under strict limitations on movements and contacts – still produced great feats of athleticism, but where once those feats were greeted by cheers, now there was just silence.

Television tried to break that silence, by pumping fake crowd noise into their production, some sports leagues in the US tried virtual crowds, but even that didn’t help, the atmosphere, never mind flat, was non-existent. Sport was silent.

That was among the most tangible effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and what it did to professional sport from a viewing perspective.

But the consequences of lockdowns and subsequent restrictions to enable professional sports to resume playing again, go much deeper than that.

Although by the middle of last year, elite sport had returned, the pandemic had wrought financial devastation. Jobs were lost, school sports stopped as did the amateur versions and recreational sport was non-existent, which is still the case.

From March to June last year the fields and courts of the sports world were empty. During that period federations, franchises and teams incurred significant losses. People died.

Major sporting events were cancelled – the biggest, the Summer Olympics scheduled for Japan, is supposed to take place this year, but it is unlikely to have visiting spectators allowed.

In South Africa the lucrative and historic tour by the British and Irish Lions has also had to be rescheduled with no dates or a venue yet finalised. That tour, with up to 40,000 spectators supposed to follow, was understood to be worth about R6 billion.

It was going to be a highlight on the South African sports calendar – the world champions against the best that the four Home Unions could muster. Sadly, if it were to take place this year it would do so without fans, an almost pointless exercise given that it’s the fans that lend so much lustre to the event, not to mention money.

There’s the big three sports in South Africa which have endured a rough passage – and areas within those sports may yet suffer permanent consequences of the pandemic – but those sports have retained a broad fan base and will be able to rely on that to – in the foreseeable future – regain some kind of financial stability.

Football, rugby and cricket can afford to create bio-secure environments to enable their events to continue.

That is not the case for everyone. For the lesser sports – hockey, netball, volleyball – the consequences could be catastrophic.

More worrying has been that youngsters have been idle for a year. Those junior club events, the school sports, have not taken place and the pandemic has kept teens and younger children indoors.

Video gaming has replaced backyard kickabouts with the neighbours, and that element – a key foundation for many children’s development – may yet have far-reaching consequences for sport.

It wasn’t just the pandemic that impacted sport.

Perhaps because so many were stuck on their sofas, the onus was on high profile athletes to shine the spotlight on social inequality that was raised by the Black Lives Matter movement.

Stemming from the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota, that social movement directly drew sport into its orbit. It had to, it was a sportsman – NFL quarterback, Colin Kaepernick – that drew attention to the discrimination and injustice endured by black people in the US.

When sports resumed around July last year, players and officials kneeled before a ball was kicked, bowled or a car was started in Formula 1. Naomi Osaka wore a different mask ahead of each of her matches at the US Open last year which had the names of black people murdered by police in the US printed on them.

In South Africa, cricket endured a painful period as the racial undercurrents in that sport erupted. Those are issues still to be resolved in the sport.

Yet the pandemic also shone a spotlight on the generosity of athletes, particularly those willing to get their hands dirty to help the downtrodden. Manchester United striker Marcus Rashford drove a change in the UK government’s policy to enable poor children to receive meals at school.

Here in South Africa, Siya Kolisi, Temba Bavuma, Faf du Plessis and Cheslin Kolbe got involved in charity endeavours to assist the less fortunate, especially those who have been hard hit by the pandemic.

Sport has still not been able to welcome back crowds. In New Zealand for a few months it was possible, but then various outbreaks demanded new lockdowns. India had crowds for the Tests involving England, but the lucrative Indian Premier League T20 competition will start next month with no crowds allowed for the first half of the tournament.

Here in South Africa, under level 1 measures pockets of gatherings are allowed, but for now, the big three sports are being understandably cautious.

It’s been a difficult year for sport and the full consequences of this pandemic may not reveal themselves for some time.

@shockerhess